Miners are frequently blamed for causing dips in the price of Bitcoin. These accusations are often unsubstantiated—worse still, they’re sometimes based on faulty metrics that conflate mining pool payouts with miner spending, ultimately misleading their users.

Accurately assessing the degree and impact of miner selling is crucial to understanding the market. In Following Flows: A Look at Miners’ On-Chain Payments, Coin Metrics unveiled a new methodology for estimating miner activity. This methodology factors in the way that pool wallets are structured, allowing users to distinguish between pool and miner activity.

In this piece, we’ll refine our miner activity estimates with data on the relationship between miners and exchanges, allowing us to determine when and where miners sell their coins. All of the metrics used in this article will be made available in our upcoming 4.9 release of Network Data Pro.

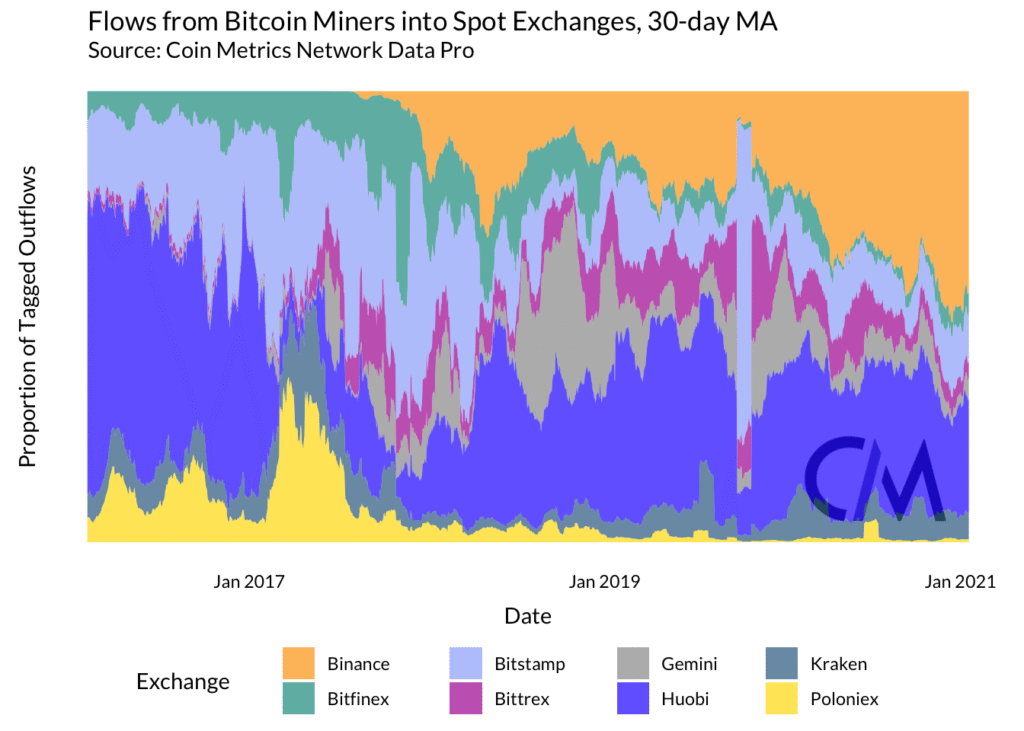

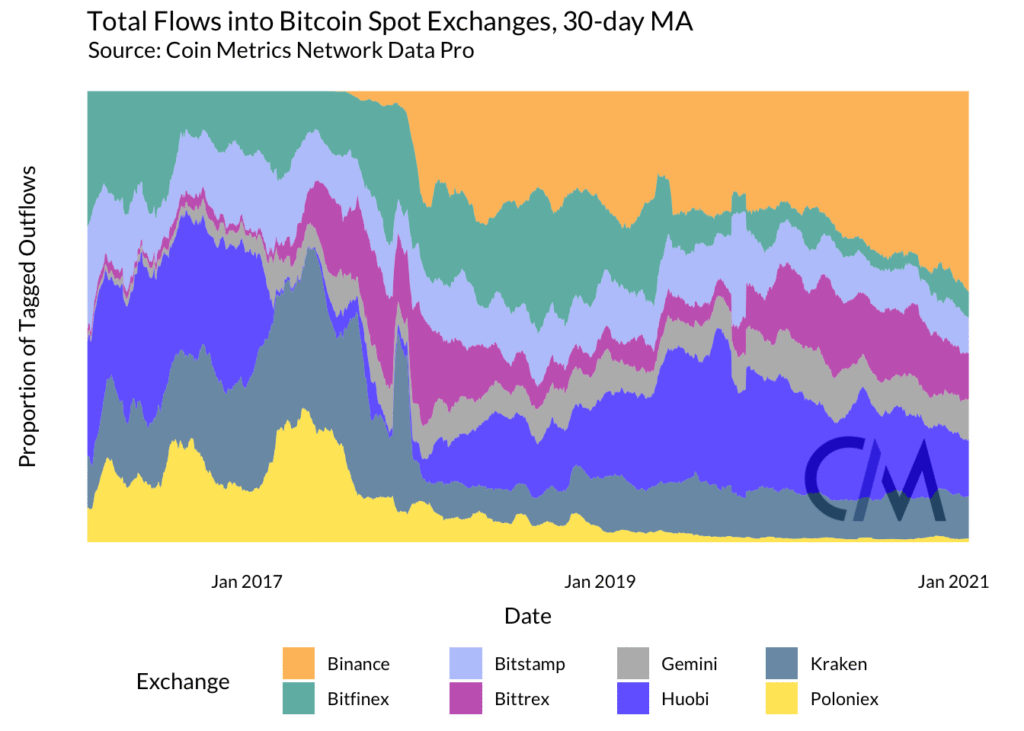

In line with the conventional wisdom, we find that miners tend to prefer Huobi and Binance to other exchanges. We also find that flows from mining addresses represent a small percentage of total exchange inflows, about 5.5% at time of writing, and are not a major source of market volatility.

Miner Marketplace Measurements

Coin Metrics’ miner-exchange flows are based on our existing estimates for miner and exchange activity. The existing inflow, outflow, and supply metrics provide useful context on market sentiment, exchange health, and network decentralization. Due to differences in their problem structures, the exchange flows and miner flows are built on two different clustering techniques, each of which has its own drawbacks.

Exchange flows are estimated using the common-input-ownership heuristic, which assumes that addresses that are inputs to the same transaction share an owner. This technique is precise, but requires at least one seed address for every exchange, limiting coverage to a predetermined universe of exchanges. The heuristic is also broken by CoinJoins and peeling chains.

Trading on a centralized exchange typically requires users to deposit coins onto the exchange, where they’re custodied by the exchange operator. Mining generally works similarly: miners share resources with one another to improve their chances of finding a block, coordinating through mining pools with centralized operators. Mining pool operators typically receive newly-mined coins to an address they control, and only later distribute them to miners through payout transactions.

Coin Metrics’ miner flows account for this architecture by basing clustering on an address’s distance in hops from the coinbase transaction. Addresses that have received a coinbase reward, or 0-hop addresses, are assumed to belong to mining pools. 1-hop addresses that have received payment from a 0-hop address are tagged as belonging to miners. This heuristic is less precise than the common-input-ownership heuristic, but roughly mirrors the structure of mining pool wallets and provides better coverage.

Neither type of clustering can detect the use of fresh addresses, and the results of each should be treated as rough estimates. Because exchange tagging is more precise, we resolve collisions in favor of that heuristic: addresses that are tagged as belonging to both a miner and an exchange are treated exclusively as an exchange.

By combining these two techniques, we can assess where miners are depositing their coins, which roughly corresponds to where they sell.

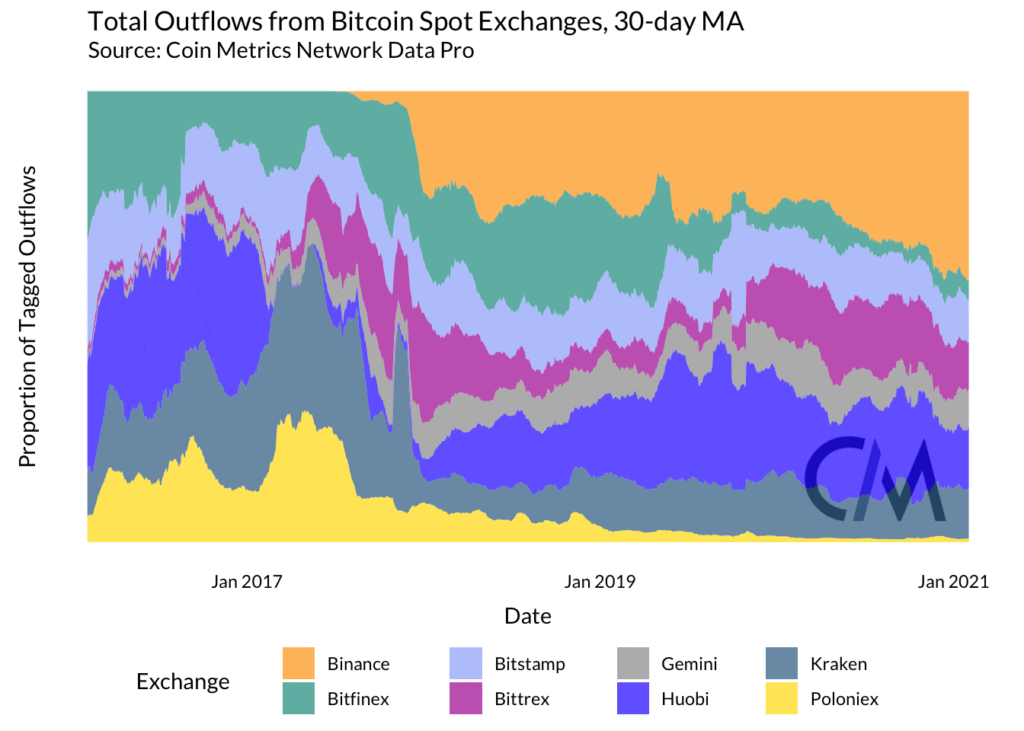

The flows from miners to exchanges are broadly similar to overall exchange inflows, but have several key differences. Binance and Huobi are by far the best-represented exchanges, with Huobi being significantly overweight in comparison to its share of overall inflows.

These results seem intuitive, since Huobi and Binance are the only two exchanges in the coverage universe that also operate mining pools. Both exchanges also have close relationships with miners, and have strong presences in Asia, where most miners are based.

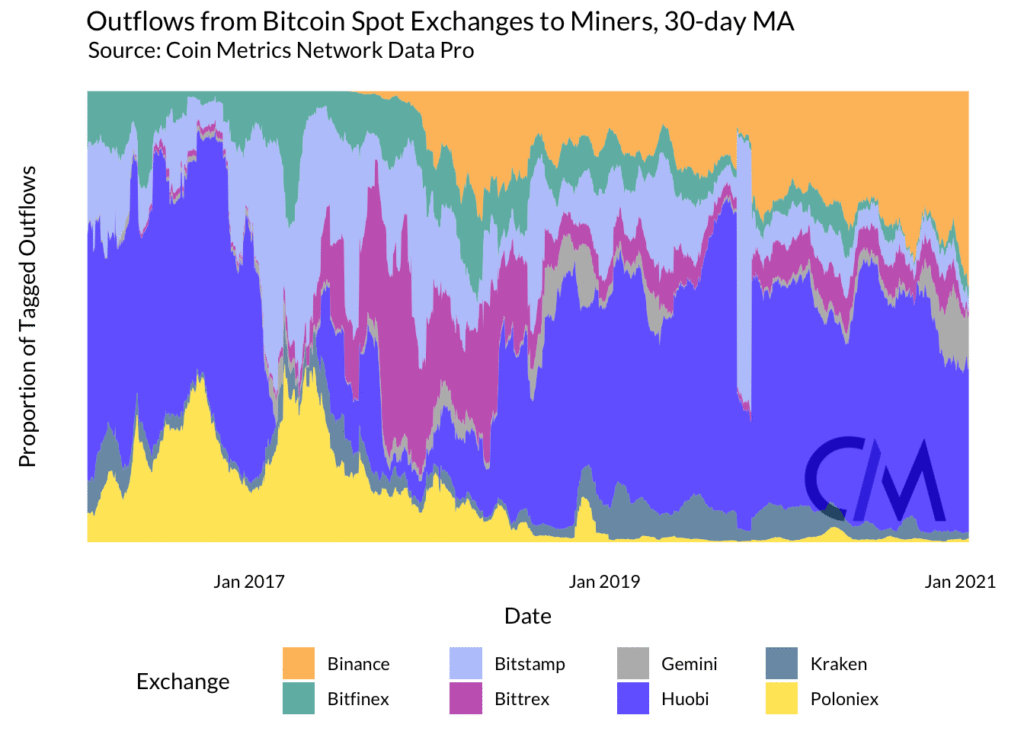

Outflows from exchanges to miners are also dominated by Binance and Huobi. This suggests that miners are buying on these venues as well.

As with inflows, Huobi is significantly overrepresented in outflows compared to the exchanges that do not operate mining pools. Binance’s share of both distributions is roughly comparable.

In the future, miner-exchange flows could be used as a proxy for the geographic distribution of mining power. This would depend on the assumption that miners use exchanges in their region, and would also require more complete exchange coverage in order to paint a representative picture.

Sizing Miner-Exchange Flows

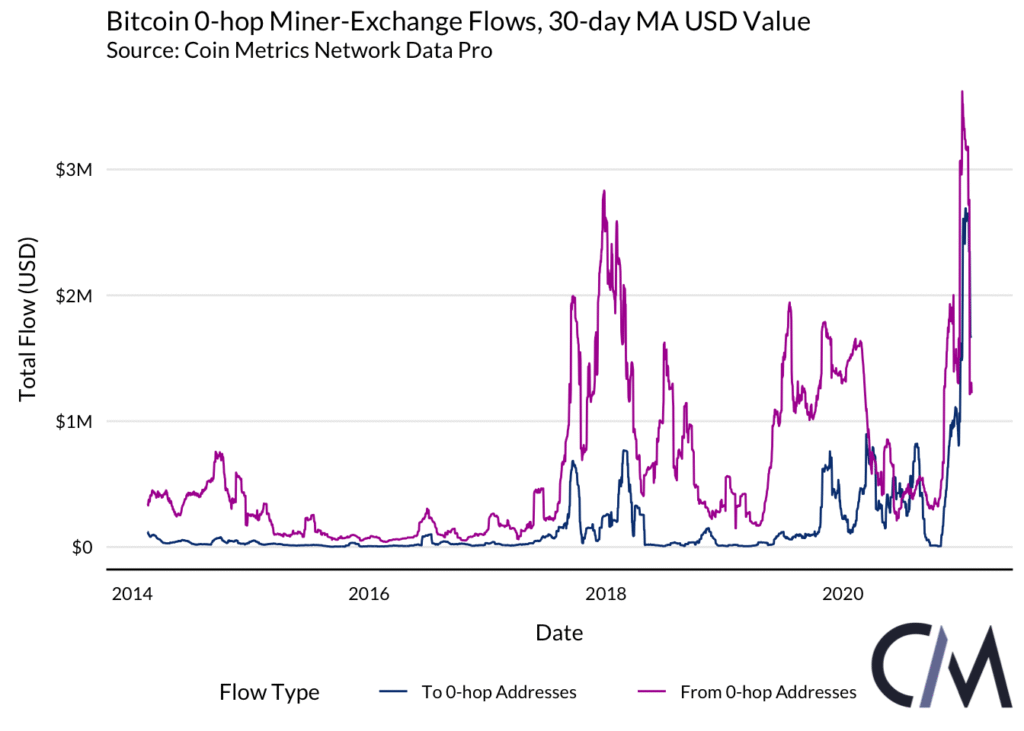

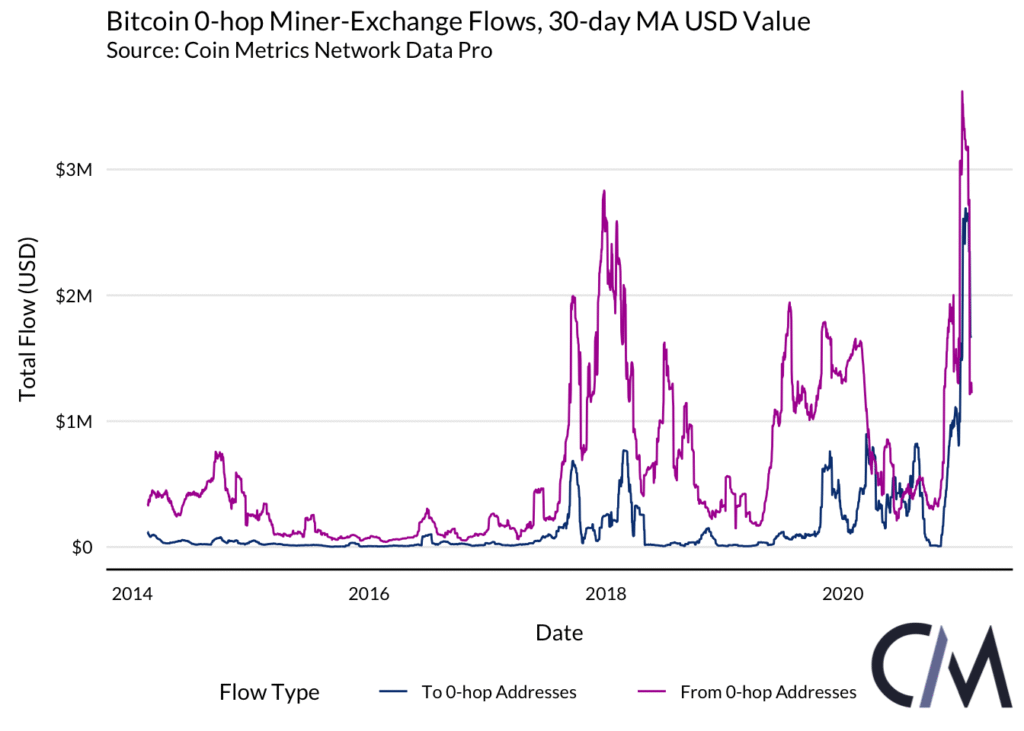

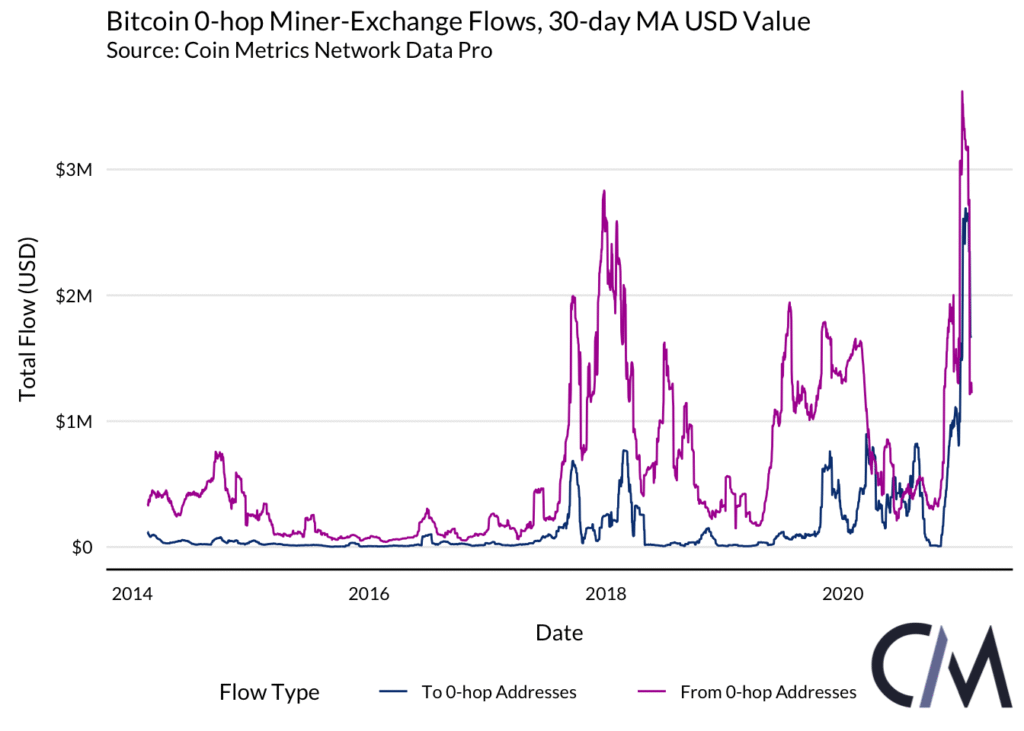

Our methodology can be used to assess both the composition of miner-exchange flows and their overall scale. On aggregate, mining pools are net depositors into exchanges, though the quantity of funds transferred daily is small.

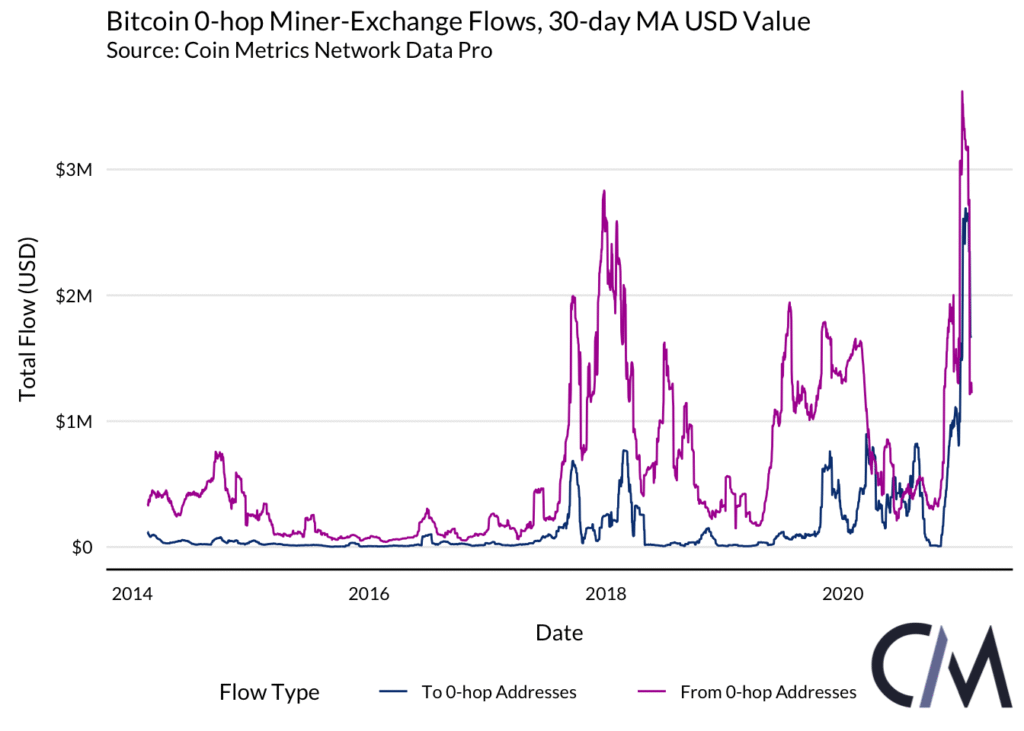

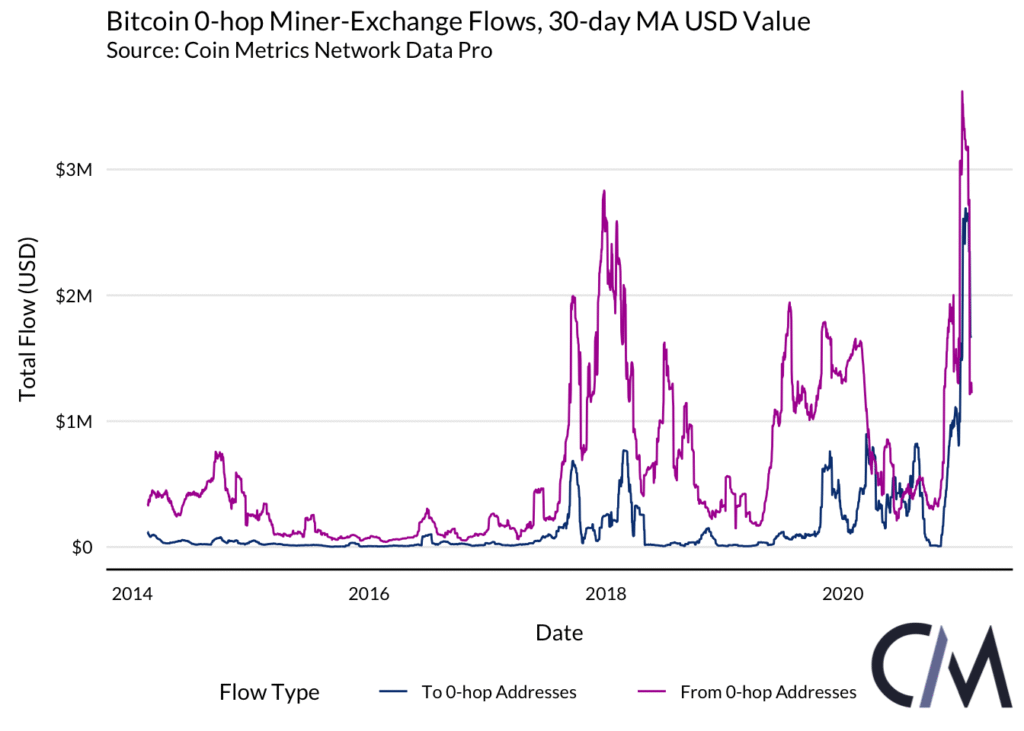

Like their respective overall flows, 1-hop miner-exchange flows are about an order of magnitude larger than 0-hop flows. While these flows have decreased in BTC terms since their peak 2016, they’ve gradually increased since 2018. In contrast, USD-denominated flows have soared past previous highs, reflecting the increase in Bitcoin’s price.

Unintuitively, miners appear to be net buyers under our assumptions. This is likely a methodological artifact stemming from multiple factors.

One contributing factor may be that most miner selling is done over-the-counter (OTC), meaning the funds are not immediately sent to an exchange. Accumulation by early miners is also probably a contributing factor, and could be resolved by filtering out flows from addresses that have not recently received funds from a 0-hop address. Finally, payouts from exchange-affiliated mining pools may be being conflated with exchange withdrawals.

In spite of this result, the aggregate flows appear directionally correct; in combination with exchange-specific flows, they’re also granular enough to be useful. Due to the consistent unexpected spread between these inflows and outflows, though, net flows calculated from these time series may be of limited value.

Flows In Context

Miner-exchange flows are best understood in the context of their constituent flows. To get a sense of the scale of miner-exchange flows, it’s helpful to compare them to total miner flows and total exchange flows.

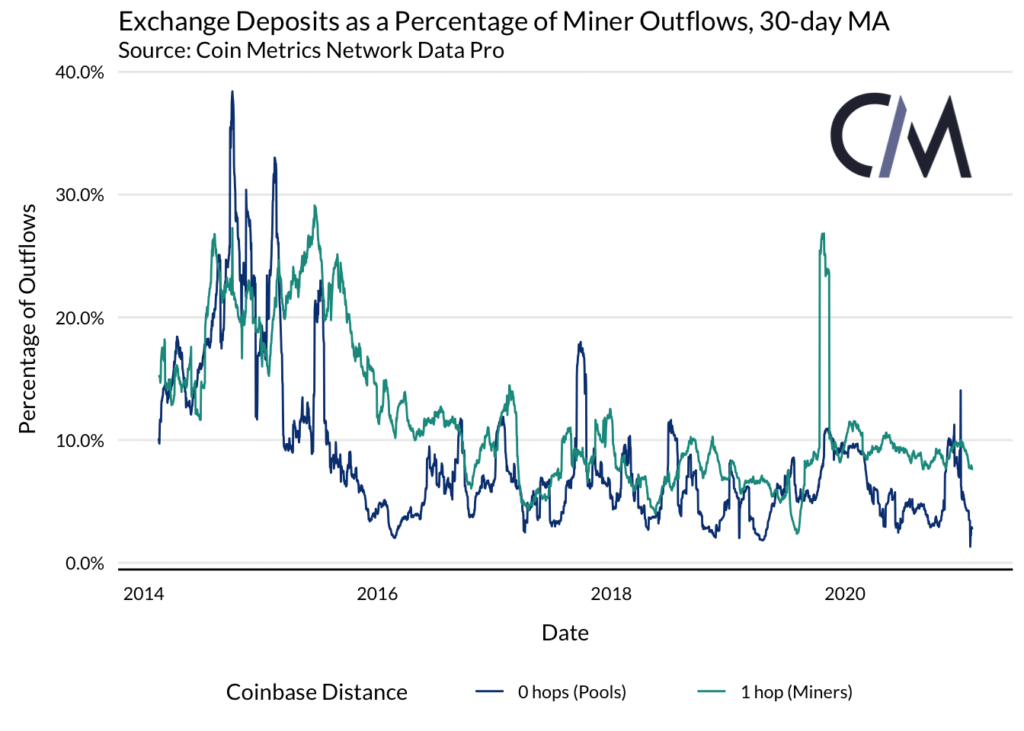

Transfers to exchanges typically represent a high single-digit percentage of miner flows, though this has varied historically. Deposits into exchanges also constitute a nontrivial percentage of pool flows.

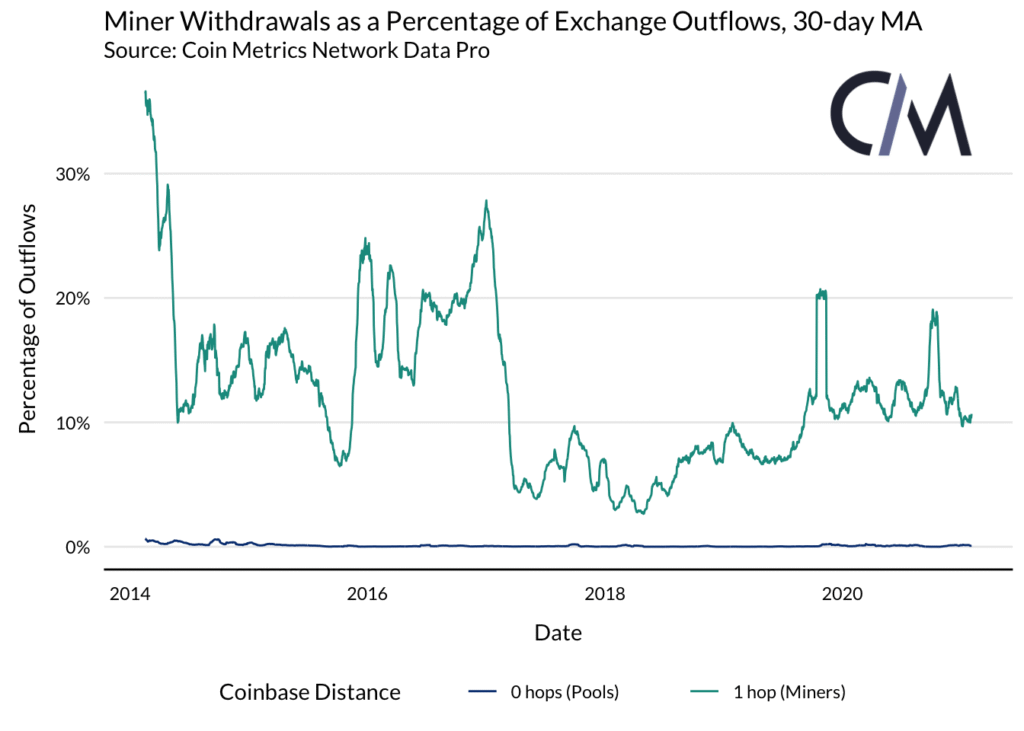

Withdrawals from exchanges represent an even higher percentage of miner inflows, likely because of payouts from exchange-affiliated mining pools and OTC selling. Withdrawals to zero-hop addresses are generally a much smaller percentage of overall flows, though they have recently begun to increase.

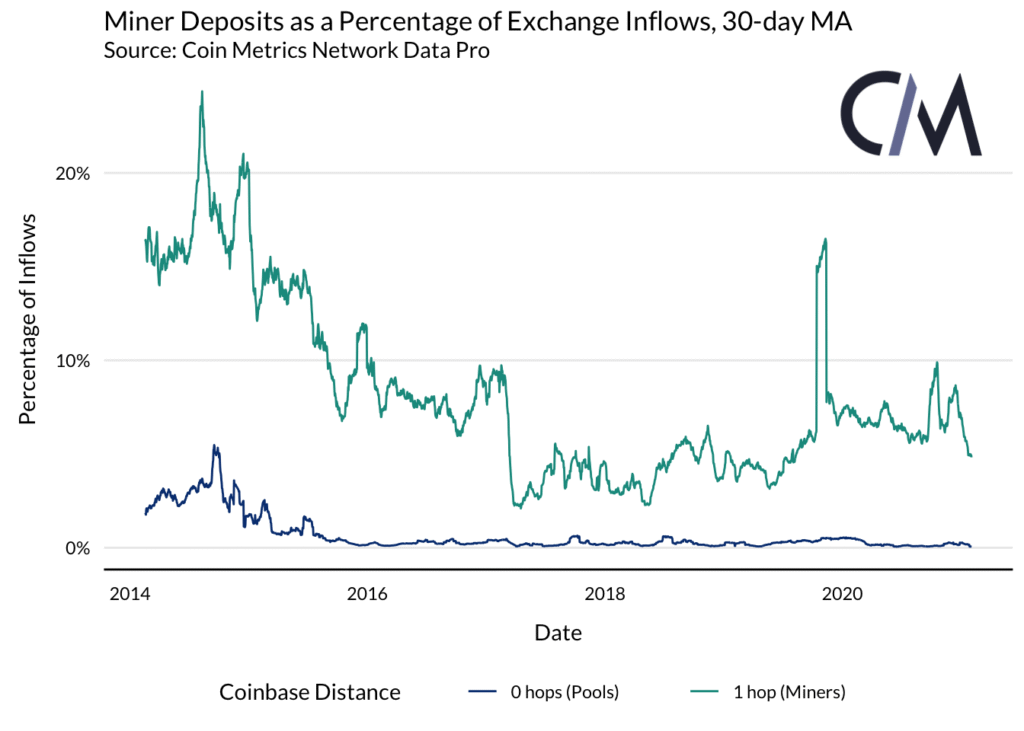

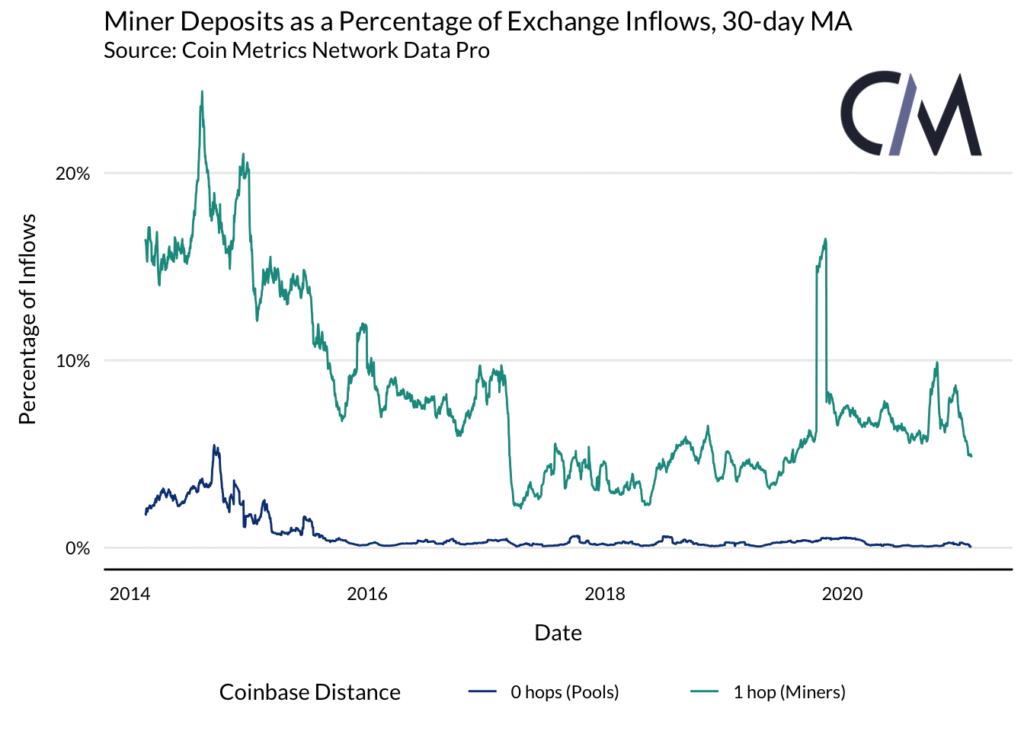

Miner deposits to exchanges, which should in theory correlate with selling, have typically represented a single-digit percentage of exchange inflows over the last few years. At time of writing, miner deposits make up about 5.5% of exchange inflows. While most miner selling is done OTC, this number is likely upward-biased due to the wide net cast by the 1-hop heuristic, meaning the true on-exchange sell pressure provided by miners is probably even lower.

While miner-exchange flows themselves are volatile, their swings are small enough to be inconsequential in the context of overall exchange flows, and flows between 0-hop addresses and exchange addresses are negligible. As a result, we see little reason to attribute downward volatility in the price of bitcoin to miner selling.

Miner withdrawals represent a larger proportion of overall exchange outflows, generally remaining above 10% in the last year. The disparity between this figure and the percentage of inflows stemming from miner deposits may be related to the role of exchange pools, which may maintain close ties to their parent companies and may pay out from overlapping addresses.

The lack of a relationship between price and miner activity is confirmed by the low correlation between price and deposits. This lack of correlation also holds when trained only on days where the price went down.

The lack of a relationship between price and miner spending can also be visually confirmed by comparing changes in price and miner deposits. These values rarely move in tandem, indicating a low correlation. While distributions of daily percent change are skewed compared to those of the underlying variables, they’re appropriate for performing an informal visual analysis.

Conclusion

The impact of Bitcoin miners on the broader market is still under-researched. By developing more refined methodologies for assessing the scale of miner activity, though, we can begin to better understand the role miners play. Given the small scale of miner deposits in comparison to total exchange flows, and the lack of correlation between miner-exchange flows and price, we find little reason to believe that miners are responsible for downturns in Bitcoin’s price.

There’s still substantial room to improve these metrics, especially with regards to increasing exchange coverage and filtering out addresses that have not recently participated in mining activity. Nonetheless, the exchange-level flows are consistent with the conventional wisdom that Binance and Huobi are the preferred exchanges for miners, informally sanity-checking the metrics’ effectiveness.

Along with several other novel metrics, miner-exchange flows will be made available in the upcoming 4.9 release of Network Data Pro. As we continue to improve our estimates of miner spending, we look forward to sharing our results and helping our users cut through the noise.